Raynaud's condition affects around 10 million in the United Kingdom every year, with Raynaud's syndrome symptoms varying from mild to severe depending on the number of digits involved. It's a highly prevalent, yet largely misunderstood, phenomenon.

In this piece, we'll be discussing some of the realities and misconceptions around it.

What is Raynaud’s Phenomenon?

Raynaud's phenomenon is a vasospastic condition in which the blood vessels within the fingers and toes narrow after exposure to cold or stress. Approximately one in every twenty people will develop Raynaud's at some time throughout their lives, although only 5% will need treating.

The condition was named following Dr. Auguste Gabriel Maurice Raynaud (1834 - 1881), identifying it in 1862. "Everytime that she went out during weather at all cool, the nose, chin, cheeks, hands and feet became pale. They passed then to a violet ting, then to a slaty white,” he wrote in his thesis.

What Causes Raynaud's Phenomenon?

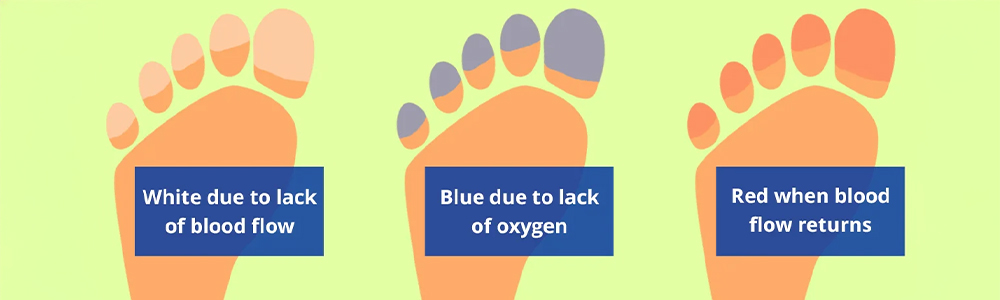

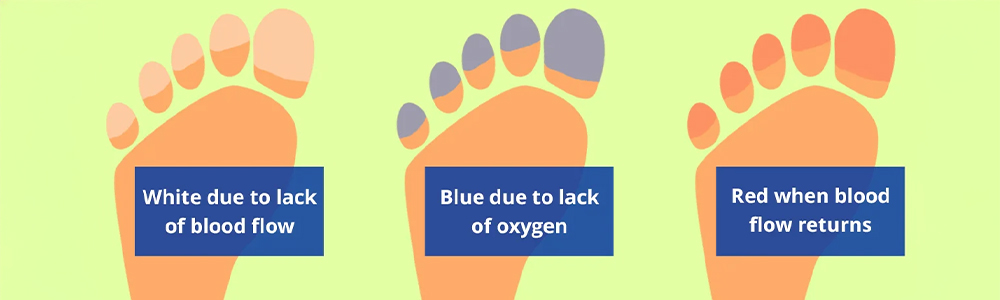

The disorder, Raynaud's phenomenon (otherwise known as secondary Raynaud’s syndrome), involves the blood vessels in the fingers and toes, but it can affect the knees and joints as well. It's a result of the blood flow to these places being diminished or obstructed because of low temperatures or stressors. The fingers and toes can turn white or blue, which dissipates as blood supply restarts. When the blood vessels contract, there may be a painful feeling known as "pinching" in more severe cases.

Raynaud's can also cause a reduction in blood supply to the ears, which can result in tinnitus, a ringing sound.

It's a cycle in which the veins and arteries that transport blood to the extremities contract and then dilate. This process normally occurs when someone is chilly or anxious, but it's more prevalent and severe in individuals with Raynaud's.

How is it Different to Raynaud’s Disease?

Raynaud’s disease, otherwise known as Primary Raynaud’s, is common, has no known cause, but is generally less severe. In most cases, Raynaud’s disease is not serious and can be treated at home. Recommendations for managing Raynaud’s include keeping your home warm, getting regular exercise, and eating a healthy, balanced diet. Raynaud’s phenomenon, or secondary Raynaud’s, is normally connected to an autoimmune disease or underlying health condition, and symptoms are more severe.

Is Raynaud's an autoimmune disease?

Often, secondary Raynaud’s are linked to autoimmune diseases including Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriasis, lupus, or scleroderma. If you are worried you may have an underlying condition, you should always consult your doctor for advice.

Myth Busting: Common Misconceptions about Raynaud’s

Myth 1: Raynaud’s means Circulation Problems

Insufficient circulation occurs when the body is unable to adequately pump blood to all regions of the body, although it's not a disorder in and of itself. Raynaud's is a vascular disease, not a circulation disorder. This indicates it affects the blood vessels rather than the respiratory system.

Myth 2: Raynaud’s syndrome is the same as Frostbite

Frostbite is when the skin is continually subjected to extremely cold temperatures. The skin grows cold and numb, gradually reddening and turning blue. Frostbite can cause irreversible skin damage in severe cases.

Myth 3: Chilblains and Raynaud's are the same

Chilblains are little red, itchy spots that develop on the skin after extended cold exposure. They’ve been most commonly found on the cheeks and ears, although they can arise anywhere on the body. Chilblains aren’t deadly, but they are unpleasant.

The Causes of Raynaud’s Phenomenon

The specific causation is unknown, however, it could be linked to a number of different factors, including:

- Age - Raynaud's tends to develop more frequently in young adult women. It’s also more prevalent in persons who have a family history of the disorder.

- Genetics – There’s some indication that specific gene mutations may be associated with Raynaud's, but further study is needed before researchers can determine.

- Autoimmune disease - Raynaud's could be induced by autoimmune diseases such as lupus or scleroderma. It may additionally occur after an injury to the feet or hands.

- Smoking - cigarettes have been linked to Raynaud's phenomenon, and quitting can help keep the condition from progressing.

Who Raynaud’s Can Affect

Raynaud's phenomenon is most commonly seen between the ages of 20 and 40, but it can happen at any time. The condition produces symptoms that often come and then go. It may not hinder your ability to work or do everyday tasks so it's possible for it to be present for some time before you realise it.

Depending on the source, the incidence varies from less than 1% of men and up to 20% of women, with women having a greater prevalence than men. According to Japanese research, this gap may be explained by differing oestrogen levels.

It also affects those who are expecting, and people who have lupus or scleroderma. If you're diabetic, you’re nearly twice as likely to develop it as individuals who do not. People who smoke also tend to be more susceptible to experiencing Raynaud's phenomenon, due to it increasing intolerance to cold temperatures and decreasing blood flow.

How do you fix Raynaud's?

There's no cure or fix for Raynaud's phenomenon, so it is just a case of keeping symptoms under control. Keeping your body warm as much as possible is usually enough to prevent attacks. Medication is not normally needed, but may be recommended by doctors in some cases.

Raynaud's Phenomenon Treatment

There's no cure for Raynaud's phenomenon. The primary objective of any therapy is to keep the severe symptoms from reoccurring. Although 95% of patients will not require medication, doctors may recommend calcium channel blockers or vasodilators to enhance blood flow in the arteries and veins. When the fingers and toes are too cold, this can help them warm up more quickly.

Here are our top 4 tips for treating Raynaud’s phenomenon at home.

- Gloves or socks with silver fibres

Wear gloves or socks infused with silver to keep your hands from becoming too chilly. Silver may transfer heat back into your skin, keeping your hands warmer than they would be ordinarily. - Gloves or socks with copper fibres

Copper is a conductive element that might also warm your cold hands. Copper woven into gloves or socks could restore heat to your skin, stopping your fingers from becoming excessively cold and uncomfortable. - Gradually warm up

As you come in from the cold weather, don't race indoors or hurry to warm yourself immediately by taking a hot bath or shower. Rather, progressively enter a heated environment and allow your body to acclimatise to the temperature difference. To stimulate blood flow, you can also hold a warm compress to your hands or feet for five minutes. - Dress warmly and comfortably

Wear loose-fitting attire made of natural fibres such as cotton or wool. These textiles maintain your body temperature better than synthetic ones like polyester. Having looser clothes also allows you to layer under your outerwear and vary how many you wear depending on the weather outside.